Actors are a programming model that is the essence of modern development for distributed systems. In this post, I will dive into why actors are an ideal choice for building backend services, describe the Dapr Actor model, and when best to use them. Actors are durable, stateful objects with self-contained compute and can be used for many applications. First, let’s go into some relevant background history of actors and why they are so appropriate for application developers.

What Are Actors?

Imagine you’re running a company that develops industrial smart lighting used in buildings, parking lots or manufacturing plants. The parking lots light up at night, buildings reduce usage when workers go home, and manufacturing plants dim lights in areas where there are few people. Each light tracks its own status—on/off, brightness level, color, and energy usage and they respond to commands from controlling services. The goal is to optimize energy usage, with motion sensors and schedules determining usage. During a typical day, some lights are idle, others are active, each controlled depending on its environment. With actors, each light can be treated as a self-contained entity, storing its state and responding to commands like “turn on,” “change brightness,” or “schedule a time to turn off.”

That’s the essence of actors: they let you scale individual pieces of stateful business logic independently and reliably.

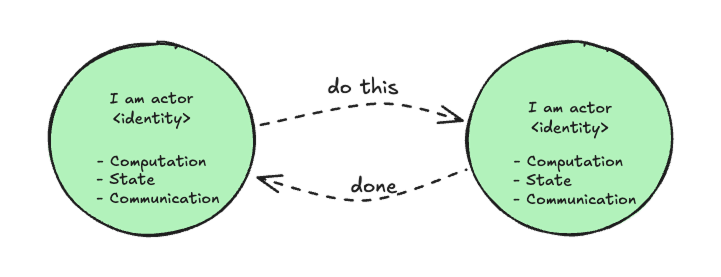

Now, if we wanted to give a more formal definition of actors, they’re objects in the domain of concurrent computation, characterized by these core properties:

- Identity — have a known, unique identity that enables actors to find each other and secure resources.

- Computation — do processing with a set of methods or behaviors that react to events.

- State — hold and modify state internally, are long-running and durable.

- Communication — can communicate with other actors.

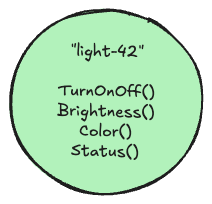

Returning to the smart light, let’s look at an example of an actor that is a software digital twin for a physical light.

- Identity — a unique UUID for the light actor type.

- Computation — methods for TurnOnOff, Brightness, Color, Status.

- State — variables representing power, brightness, color, status, make.

- Communication – receives calls from client and other actors to change the light.

This might sound just like classic object-oriented programming (OOP) concepts: an instantiated class (object) also has identity, behavior, state, and can call other objects. But the big difference is the scope. Objects exist inside a single local process, while actors are distributed across the entire compute cluster. An actor instance is not tied to any single local process; it’s globally addressable and distributed. An actor is still just a piece of code, like an OOP object and there can be thousands of them running in a single process. These processes are then distributed across many machines in the cluster. Kubernetes and other distributed container platforms are an ideal host platform to deploy actors to.

Drawing this parallel between the actor model and familiar OOP concepts makes it easier to understand. Turns out, this wasn’t just a random mental shortcut. The original ideas for the Actor Model itself were introduced by Carl Hewitt in the 70s [1][4], and it emphasized message passing and concurrency—something that resonates with modern distributed systems. We just needed the hardware and communication to reach a level of maturity that the cloud provides today. In the early 1970s, as object-oriented programming was taking shape in Smalltalk, Alan Kay (often recognized as the father of OOP) was influenced by the ideas from the Actor Model.

“Actors in the Actor Model embody not only state but also behavior. This might sound suspiciously like the definition of OOP; in fact, the two are very closely related. Alan Kay, who coined the term object-oriented programming and was one of the original creators of the Smalltalk language, was largely influenced by the Actor Model. And while Smalltalk and OOP eventually evolved away from their Actor Model roots, many of the basic principles of the Actor Model remain in our modern interpretation of OOP.” — The Actor Model - Applied Akka Patterns by Michael Nash, Wade Waldron (O’Reilly)

This quote presents a unidirectional view, but the object-oriented programming and the Actor Model developed in close dialogue with each other. Alan Kay was notably inspired by Carl Hewitt’s work on the Actor Model, while Hewitt himself drew insights from the message-passing foundations in Smalltalk and the emerging concepts of objects and encapsulation. As a result, the two paradigms have been feeding ideas into each other since the 1970s, integrating message-passing and distributed thinking more deeply into what eventually became modern OOP and the Actor Model.

The Virtual Actor Model

Compared to most concurrency strategies of the time—which relied on shared memory and locking—Carl Hewitt’s Actor Model emphasized message passing and state isolation. In the original model, developers created actors explicitly by making a direct call to its address and decided when and how that actor was destroyed, making lifecycle management the developer’s responsibility. Typically, the actor’s state lived in local memory, so scaling up or managing failover required additional logic to move or replicate that state. Furthermore, to communicate with an actor, the system usually generated or exposed an address (or reference), and scaling or distributing actors often depended on custom mechanisms that could resolve these references across multiple nodes. In other words, there was no direct concept of actor identity. Just like malloc and alloc in C, or New and Delete in OOP before the advent of managed languages like Java, actor lifecycle management was unwieldy for developers.

In 2008, a paper from Microsoft Research instead described the concept of a Virtual Actor Model [2]. With the virtual actor Model, the runtime automatically manages each actor’s lifecycle, so developers no longer had to handle the creation or destruction manually. This is like garbage collection in OOP programming languages. This approach also avoids wasting memory on idle actors by deactivating them when they’re not in use and persisting their state. The actor state is typically stored in an external persistent storage, allowing for unlimited growth, but is also cached in memory. Because an actor’s state can be unloaded from one location and reloaded on another, it’s easy to move actors around, enabling scaling. In the virtual actor model, an actor’s unique identifier is no longer its physical address. Instead, it’s defined by a combination of actor type and an actor id. When a developer invokes an actor, they simply provide that unique identity pair. The system takes care of finding (or activating) the actor on whichever machine is appropriate, eliminating the need for developers to track physical addresses like IP address, ports, etc.

The first implementation of this virtual actor model was the Microsoft Orleans project [2]. Another implementation was built into Microsoft Azure Service Fabric [3], from which the Dapr Actors [6] implementation is directly taken. Dapr has included actor support since its very first release, recognizing the utility in distributed applications. The Dapr Actor model greatly expanded on the virtual actor model, implementing it in multiple languages, providing a consistent HTTP API with which actors could be managed, optimizing it on run on Kubernetes, providing automatic clean-up of the state storage with timeouts, enabling swapable backing state stores and many other capabilities. At the heart of Dapr Actors has been simple to use SDKs to create actor types and let the Dapr runtime do all the heavy lifting of actor creation, distribution, reminders and timers scheduling and handling failures. Today, Dapr has the most comprehensive, easy to use actor API of any framework, and it continues to evolve with each release. In today’s era of online services and cloud computing, distributed compute platforms like Kubernetes can now had to handle millions of Dapr virtual actors in an elastic way, being able to dynamically scale up and down, and provide long-running durable objects, perfect for developing IoT systems like our lighting example, business workflows and event-driven applications. Furthermore, as we will also see that Dapr Workflows builds on Dapr Actors to provide an even higher level of abstraction, suitable for mission-critical business workflows.

Using Dapr Virtual Actors

Let’s create a Light actor to explain this with an example. You can use any of the Dapr SDKs, including Go, Java, JavaScript, Python, and .NET. I am going to use .NET for this example, but they are all similar. Let’s define an actor type with an interface ILight with methods to get and change the brightness. I prefer to have a public data class LightData to represent the state of the Light actor, which contains variables for the brightness and an autodim timer period setting.

using Dapr.Actors;

namespace Light.Interfaces;

public class LightData

{

public string Brightness { get; set; } = "brightness";

public string AutoDimReminder { get; set; } = "autodim";

public LightData() { }

public LightData(string brightness, string autoDimReminder)

{

Brightness = brightness;

AutoDimReminder = autoDimReminder;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return $"Light data(Brightness: {Brightness})";

}

}

public interface ILight : IActor

{

Task<int> IncreaseBrightnessAsync(int delta);

Task<int> DecreaseBrightnessAsync(int delta);

Task<int> GetBrightnessAsync();

Task ResetAsync();

}

The actor implementation is shown below. When implementing the ILight actor, adding the IRemindable interface means that this actor can use reminders (more on this later) to enable the Dapr runtime to wake it up periodically. Here we register a reminder called AutoDimReminder when the actor is activated in the OnActivateAsync(), which as its name implies, dims the light automatically over time when the ReceiveReminderAync() method is called by the Dapr runtime.

using Dapr.Actors.Runtime;

using Light.Interfaces;

namespace Light.Service;

public class LightActor : Actor, ILight, IRemindable

{

private readonly LightData _lightData;

public LightActor(ActorHost host) : base(host)

{

_lightData = new LightData();

}

public async Task<int> IncreaseBrightnessAsync(int delta = 1)

{

var has = await StateManager.TryGetStateAsync<int>(_lightData.Brightness);

//increase brightness and save to state store

var next = (has.HasValue ? has.Value : 0) + delta;

await StateManager.SetStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, next);

return next;

}

public async Task<int> DecreaseBrightnessAsync(int delta = 1)

{

var has = await StateManager.TryGetStateAsync<int>(_lightData.Brightness);

//decrease brightness and save to state store

var next = (has.HasValue ? has.Value : 0) - delta;

await StateManager.SetStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, next);

return next;

}

public Task<int> GetBrightnessAsync() => StateManager.GetOrAddStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, 0);

public async Task ResetAsync() => await StateManager.SetStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, 0);

protected override async Task OnActivateAsync()

{

await RegisterReminderAsync(

_lightData.AutoDimReminder,

null,

dueTime: TimeSpan.FromSeconds(1),

//period: TimeSpan.FromMinutes(10));

period: TimeSpan.FromSeconds(20));

}

public async Task ReceiveReminderAsync(string reminderName, byte[] state, TimeSpan dueTime, TimeSpan period)

{

if (reminderName == _lightData.AutoDimReminder)

{

var current = await StateManager.GetOrAddStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, 0);

if (current > 0)

{

await StateManager.SetStateAsync(_lightData.Brightness, current - 1);

Logger.LogInformation($"[{Id}] Auto-dimmed brightness to {current - 1}");

}

}

}

}

To use this actor, all you have to do is register the actor type with Dapr using a web application, so we can then create actor instances from a client.

using Light.Service;

var builder = WebApplication.CreateBuilder(args);

// Ensure WebHost binds to the port Dapr expects

builder.WebHost.UseUrls("http://0.0.0.0:5008");

// Configure logging

builder.Logging.ClearProviders();

builder.Logging.AddConsole();

builder.Logging.AddDebug();

builder.Services.AddActors(options =>

{

options.Actors.RegisterActor<LightActor>();

// Optional runtime tuning:

// options.ActorIdleTimeout = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(5);

// options.ActorScanInterval = TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30);

// options.DrainOngoingCallTimeout = TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30);

// options.DrainRebalancedActors = true;

});

var app = builder.Build();

// Add logging middleware

app.UseRouting();

app.MapActorsHandlers();

app.MapGet("/", (ILogger<Program> logger) =>

{

logger.LogInformation("ActorService is up and running");

return "ActorService is up and running. You can now create LightActors using a client.";

});

app.Run();

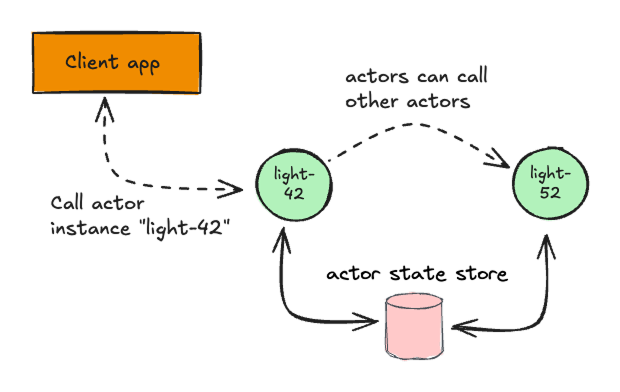

Now, let’s create a client app to create and use a Light actor. First the client creates an actor instance called “light-42” and then calls the increase and decrease brightness methods. Realize that this actor can literally be anywhere in your cluster and in fact it could have even failed and moved between machines. And there can be thousands of these actors on a resource-constrained cluster, such is their lightweight nature.

The client then performs a concurrency test, increasing the brightness from ten separate tasks. With actors, you do not have to concern yourself about multi-threading, since all methods are automatically made concurrent, thereby ensuring state consistency. This is one of their defining features. Finally, the auto dim reminder slowly dims the lights every 20 seconds with a reminder timer that is checked every 2 seconds until the light turns off.

using Dapr.Actors;

using Dapr.Actors.Client;

using Light.Interfaces;

class Program

{

static async Task Main()

{

var actorType = "LightActor";

var actorId = new ActorId("light-42");

var proxy = ActorProxy.Create<ILight>(actorId, actorType);

Console.WriteLine($"ActorProxy created, proxy: {proxy}, actorId: {actorId}");

Console.WriteLine("Increasing brightness...");

var v1 = await proxy.IncreaseBrightnessAsync(1);

Console.WriteLine($"After IncreaseBrightnessAsync(1): {v1}");

var v2 = await proxy.IncreaseBrightnessAsync(10);

Console.WriteLine($"After IncreaseBrightnessAsync(10): {v2}");

var v3 = await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"After GetBrightnessAsync(): {v3}");

Console.WriteLine("Decreasing brightness...");

var v4 = await proxy.DecreaseBrightnessAsync(1);

Console.WriteLine($"After DecreaseBrightnessAsync(1): {v4}");

var v5 = await proxy.DecreaseBrightnessAsync(1);

Console.WriteLine($"After DecreaseBrightnessAsync(1): {v5}");

var v6 = await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"After GetBrightnessAsync(): {v6}");

Console.WriteLine("Reset the brightness to 0...");

await proxy.ResetAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"After reset: {await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync()}");

//Concurrent test

Console.WriteLine("Concurrent brightness test. " +

"Everyone is increasing the brightness at the same time, but the brightness can only be updated sequentially. Only one switch!");

var tasks = new Task<int>[10];

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++)

{

tasks[i] = proxy.IncreaseBrightnessAsync(1);

}

await Task.WhenAll(tasks);

var initialBrightness = await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"After 10 concurrent calls: {initialBrightness}");

//Let's slowly dim the lights and monitor AutoDim reminder

Console.WriteLine("\nMonitoring AutoDim reminder (brightness decreases every 10 seconds)...");

Console.WriteLine("Press Ctrl+C to stop monitoring.\n");

var cancellationTokenSource = new CancellationTokenSource();

Console.CancelKeyPress += (sender, e) =>

{

e.Cancel = true;

cancellationTokenSource.Cancel();

Console.WriteLine("\nStopping monitor...");

};

var lastBrightness = initialBrightness;

var checkInterval = TimeSpan.FromSeconds(2); // Check every 2 seconds

try

{

while (!cancellationTokenSource.Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

var currentBrightness = await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync();

var timestamp = DateTime.Now.ToString("HH:mm:ss");

if (currentBrightness != lastBrightness)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[{timestamp}] Brightness changed: {lastBrightness} → {currentBrightness}");

lastBrightness = currentBrightness;

if (currentBrightness == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine($"[{timestamp}] Light has been fully dimmed!");

break;

}

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine($"[{timestamp}] Brightness: {currentBrightness}");

}

await Task.Delay(checkInterval, cancellationTokenSource.Token);

}

}

catch (OperationCanceledException)

{

Console.WriteLine("\nMonitor stopped by user.");

}

var finalBrightness = await proxy.GetBrightnessAsync();

Console.WriteLine($"\nLights Out: {finalBrightness}");

}

}

Benefits of using Dapr Actors

Dapr runs as a sidecar to your application, providing all the advantages of a resilient architecture with the separation of concerns from your application code. Once the sidecar is aware of which actor types your app can host, it handles all the heavy lifting: determining which node an actor lives on, ensuring single-threaded execution for concurrency, managing timers and reminders, persisting actor state in your chosen store, deactivating idle actors, automatically rebalancing actors during failures or system rescales and more.

All the low-level distribution, concurrency, and orchestration details happen under the hood, letting you keep your attention on the business logic.

Schréder: a real-world actors case study

This case study from Schréder Hyperion implements an intelligent lighting system using actors to manage millions of lights for smart cities and is well worth a read.

Actor best practices. When and when not to use them.

The actor model is a perfect fit for domains made up of many small, independent entities, each with its own state and behavior. Classic examples include shopping carts, IoT devices, players in a game world, AI agents or long-lived workflows. In these scenarios, each entity operates in isolation, and the guarantee that only one request at a time will be processed per actor instance is a distinct advantage. You don’t have to worry about locking, race conditions, or orchestrating concurrency.

Where actors become problematic is when they’re forced into situations they weren’t designed for. If your system is mostly stateless, or if you have only a handful of “hot” endpoints that receive massive traffic, the single-threaded nature of actors becomes a bottleneck rather than a benefit. Likewise, if your workflow requires strong consistency across multiple entities or if you’re doing large-scale streaming they are not the best approach.

Managing State Effectively

Because actors are stateful by design, it’s tempting to put whatever you want in an actor’s state store. But restraint pays dividends. Actor state should remain small and focused, containing just the data relevant to that specific entity. Large documents, blobs, logs, or aggregated data can inflate latency and introduce unnecessary overhead. If you find yourself cramming huge structures into an actor, it’s often a sign that the actor is doing too much or that some data belongs in a separate database or service.

Minimizing state writes is equally important. Every write is a remote call to a state store, which means it has a cost in terms of latency and throughput.

Perhaps the most common performance issue occurs when an actor method tries to do too much. Because actors process calls one at a time, any long-running computation or external network call blocks other requests for that actor. Heavy tasks should be offloaded to background services, worker queues, or pub/sub consumers. Actors are best when they remain lightweight—not the executors of significant data processing or I/O work.

Actor Communication

Actors communicate through Dapr’s service invocation API, and the actor SDKs make calling another actor as simple as calling a local method. While this makes code look clean, it’s important not to mistake that ease for a guarantee of efficiency. If your system develops long chains of actor-to-actor calls—for example, Actor A calling Actor B, which then calls Actor C—you can easily end up with tightly coupled flows.

Understanding Lifecycles and Failure Modes

Developers new to Dapr actors are sometimes surprised by how fluid actor lifecycles are. Actors activate on demand, stay alive while they’re used, and quietly deactivate after a period of inactivity. They might also be reactivated on a different app instance after a redeploy or scale-out event. This means you should never rely on constructors or in-memory fields to hold important state. If it’s important, it must be persisted; otherwise, assume it could disappear at any time.

Similarly, actors should be designed with failure in mind. State store calls may fail, reminders may retry, and external services may be unavailable. Making actor logic idempotent, validating assumptions, and designing around retries produces far more resilient systems. A well-designed actor should be able to resume correctly even if the node it was running on disappears mid-operation.

To understand best practices when actors, watch Harnessing Dapr Actors: Building Scalable Applications with Confidence

Under the hood of actor activation

Now let’s do an in-depth look at how Dapr's actor implementation works for some background. You do not need to know this to use Dapr actors, but it is useful to understand.

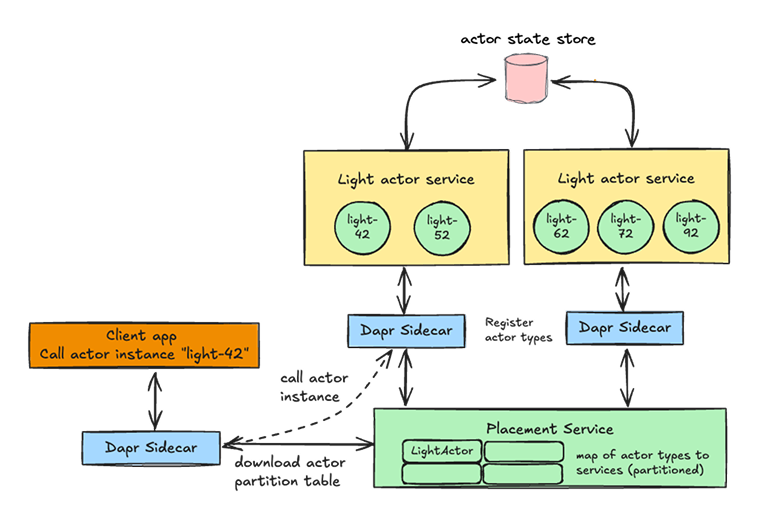

Let’s first dive into actor usage. There are three stages to using actors - registration, instance creation and client calling. In Dapr the control plane Placement service is central to this process. The Dapr Placement service is responsible for managing the distributed placement and membership of Dapr actors. Its role is to ensure that actors are efficiently and consistently distributed and discoverable across a cluster. This service is designed for high availability and strong consistency, relying on the Raft consensus algorithm for state replication and secure communication via mTLS to Dapr sidecars.

The Placement Service acts as a central authority within the Dapr control plane, maintaining a global view of where actors and other components are hosted. When new services (applications) are created, their Dapr sidecars report the types of actors they host to the Placement service. In turn, the Placement service uses this information to build a consistent mapping of actor types to the specific service instances. Then, when a client needs to interact with an actor, its Dapr sidecar queries its local placement information to determine which Dapr instance is hosting the target actor, a process called actor ID lookup.

When a new instance of a service is created, its Dapr sidecar registers the actor types it can create with the Placement service. The Placement service calculates the partitioning across all the instances for a given actor type. This partition data table for each actor type is updated and stored in each Dapr instance running in the cluster, and changes dynamically as new instances of actor services are created and destroyed. For Kubernetes by default, new actor instances are randomly placed into pods on nodes, resulting in uniform distribution.

When a client calls an actor with a particular ID, for example, light-42, the Dapr instance for the client hashes the actor type and actor id and uses the information to call onto the corresponding Dapr instance that can serve the requests for that actor ID. See the dotted line in the diagram below, which uses the Dapr Service Invocation API to call the methods on the actor. As a result, the same partition (or service instance) is always called for any given actor ID.

In summary, when a service using actors starts:

- Each Dapr sidecar for a service connects to the Placement service - the sidecar announces, “I can host these actor types.”

- The Placement service builds a global table - it keeps track of all participating nodes and their services.

- The Placement service computes actor placement using hashing - for a given actor ID, it computes a placement location based on a consistent hashing algorithm.

- The placement tables are pushed to all sidecars - every sidecar learns where any actor should be located.

- Actor activations and calls follow the decision

If you want to understand the Placement service even more, then watch The Dapr Actors Journey: From Understanding to Intuition

Under the hood for Timers and Reminders

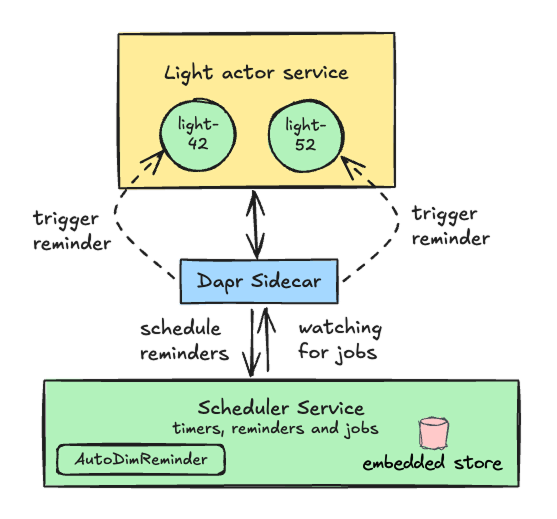

Actors can schedule future work with timers and reminders. Actor Timers are in-process callbacks scheduled by the actor itself and are ephemeral in that they are used for short-lived events whilst the actor is in memory. Actor Reminders, on the other hand, are durable, persistent and fire even if the actor is deactivated. Both let actors run code in the future or on a recurring basis. The auto dim feature of the ILight actor uses a reminder. So how does this work? That’s where the Dapr Scheduler service comes in. The Scheduler is a Dapr control plane service responsible for centralized, reliable scheduling of jobs. It ensures that timers and reminders fire exactly when they should, where only the node hosting the actor processes gets the trigger event. It plays the same role for actor scheduling that the Placement service plays for actor activation.

The Scheduler runs as a stateful Dapr control-plane service, and it coordinates actor timers and reminders. An actor registers a timer or reminder. When an actor calls RegisterTimerAsync or RegisterReminderAsync, the local Dapr sidecar sends a scheduling request to the Scheduler service so it can track and manage the upcoming scheduled event.

Once the request is received, the Scheduler stores and manages the event. For each timer or reminder, it maintains the actor type and actor ID, due time, repeat period, payload, and whether the entry is durable. Reminders are durable and persisted, meaning they survive restarts, while timers do not persist and stop when the actor deactivates. The Scheduler then determines when triggers should fire, ensuring global timing accuracy. It prevents duplicate executions and coordinates execution across the cluster. It can even handle scheduled events correctly when all actor host services are temporarily offline. When the scheduled fire time arrives, the Scheduler emits a trigger event. This event is delivered to the Dapr sidecar hosting the actor at that moment. If the actor has moved due to placement changes, the Scheduler automatically sends the trigger to the new node instead. This ensures that scheduled logic remains consistent and reliable even when actors migrate within the cluster. This is shown in the diagram below, demonstrating how each actor instance has an instance of an AutoDimReminder:

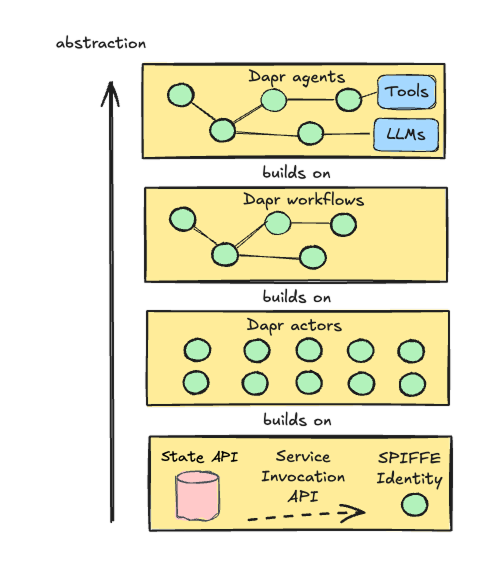

From Actors to Workflows to Agents

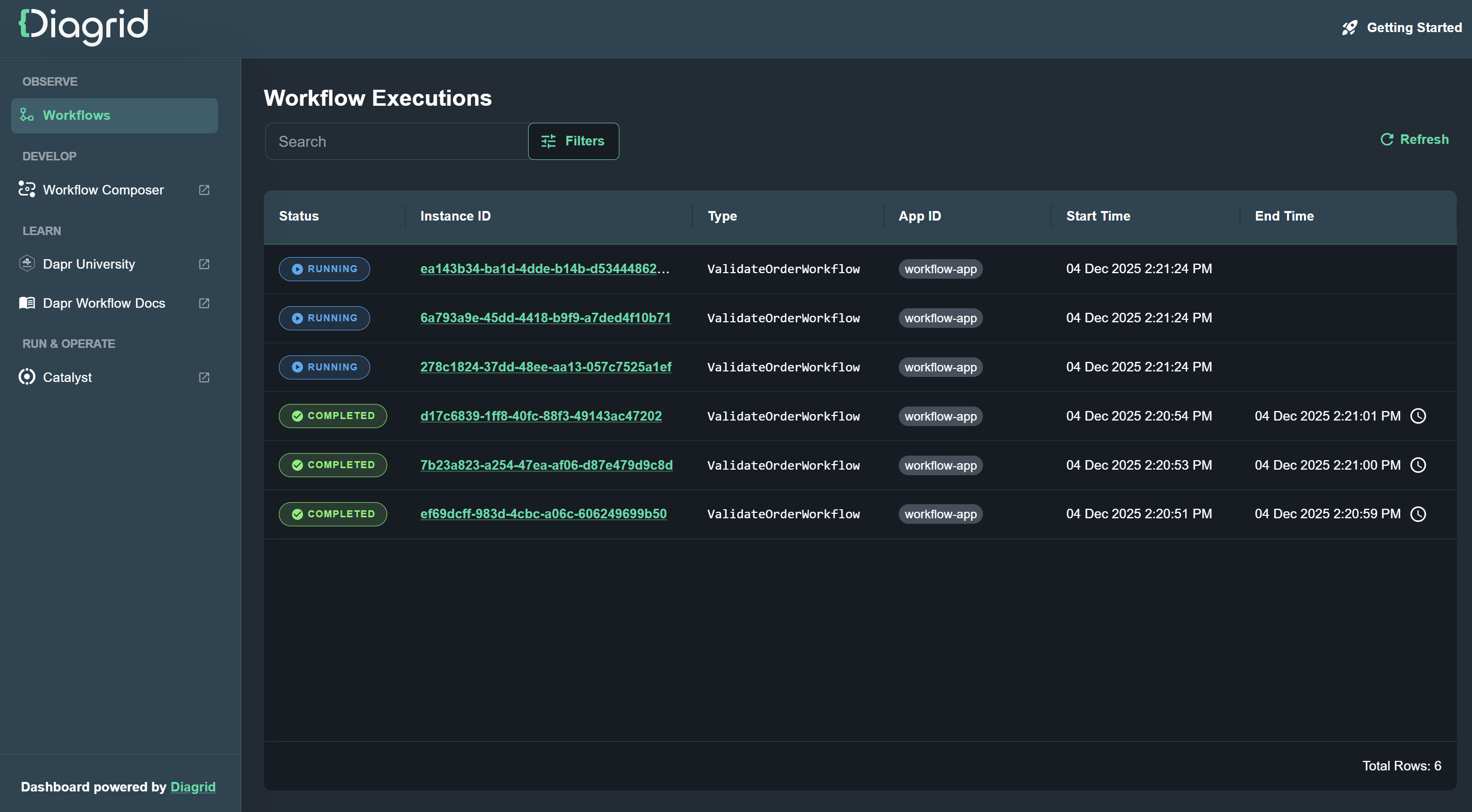

One common actor usage is building a long-running, stateful business process where different actors perform specific pieces of work. Sounds like a workflow, and it is. Actors are so good at maintaining state and scale that they are the basis of Dapr Workflow [7], which provides a higher-level orchestration model. Workflows consist of a set of activities, and each workflow (along with its activities) is represented by an actor instance, with an ID, like this sequence of three sequential activities.

So, where Dapr Actors give you stateful objects; Dapr Workflows uses those to create a higher-level orchestration model with all the benefits of workflow patterns. You write workflows in .NET, Java, JS, Python, and Go using a workflow SDK. This becomes “code as workflow” with an event stream that the workflow actors persist and can replay. You can think of it like this. Actors are the stateful, single-threaded, addressable objects with timers/reminders and Workflows are an opinionated runtime that uses actors to give you durable, resumable orchestration.

We won’t do a deep dive here; however internally, the Dapr workflow engine uses two actor types:

Workflow actors have an actor per workflow instance. They have the history log of the workflow (event-sourced style), decide which step to run next (activities, child workflows, timers, event waits, etc.), and use the turn-based concurrency from the actors runtime, so each workflow progresses deterministically and single-threadedly.

Activity actors which are created when a workflow schedules an activity task, each contain an application’s activity and send the result back to the parent workflow actor before they deactivate themselves (they’re short-lived and highly distributed). That means activities are mediated as actors; you don’t call the activity directly from the workflow actor – you schedule it, and an activity actor runs it.

That means that although actors are an effective programming model for workflow scenarios, in nearly all cases Dapr workflows are better and certainly easier to use. The same applies for Dapr Agents which build on Dapr Workflow to have long-running, AI agents that reason with tools, but that is another future post!

You can read more about converting deterministic workflows into agentic ones in “Durable Agentic Workflows with Dapr” [18]

Start Acting!

This article touched on an overview of Dapr Actors and like all technologies, it is best explored by building. Dapr Actors take the messy parts of distributed systems state, concurrency, placement, failures and make them disappear. You get single-threaded simplicity with cloud-scale power. It’s OOP for the distributed era, and it just works.

The code is available here https://github.com/diagrid-labs/dapr-dotnet-actors or for a similar example, go to https://github.com/diagrid-labs/dapr-actor-demos/. Or clone the sample code from the Dapr SDK examples in the reference.

Experiment with reminders, timers, and actor-to-actor calls, and see how easily your logic scales across a cluster. Once you’re comfortable with actors, build a Dapr workflow to discover how these stateful objects help you design robust, scalable, real-world systems with surprising ease. Enjoy.

If you have any questions about Dapr Actors, join the Dapr Discord, where thousands of Dapr developers come to ask questions and help other community members.

References

[1] Actor Model of Computation: Scalable Robust Information Systems - Carl Hewitt - https://arxiv.org/abs/1008.1459

[2] Orleans Virtual Actor Model - https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Orleans-MSR-TR-2014-41.pdf

[3] Reliable Actor Azure Service Fabric - https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/service-fabric/service-fabric-reliable-actors-introduction

[4] Carl Hewitt discussing the actor model - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7erJ1DV_Tlo

[5] Actor model - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Actor_model

[6] Dapr Actors - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/building-blocks/actors/actors-overview/

[7] Dapr Workflows - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/building-blocks/workflow/workflow-overview/

[8] Dapr Agents - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/building-blocks/workflow/workflow-overview/

[9] Harnessing Dapr Actors: Building Scalable Applications with Confidence - https://www.diagrid.io/videos/harnessing-dapr-actors-building-scalable-applications-with-confidence---whit-waldo-ceo-innovian

[10] The Dapr Actors Journey: From Understanding to Intuition - https://www.diagrid.io/videos/dapr-day-the-dapr-actors-journey-from-understanding-to-intuition

[11] Java Dapr Actors examples - https://github.com/dapr/java-sdk/tree/master/examples/src/main/java/io/dapr/examples/actors

[12] Python Dapr Actors examples - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/sdks/python/python-actor/#actor-client

[13] .NET Dapr Actors examples - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/sdks/dotnet/dotnet-actors/dotnet-actors-howto/

[14] JavaScript Dapr Actors examples - https://docs.dapr.io/developing-applications/sdks/js/js-actors/

[15] Go Dapr Actors examples - https://github.com/dapr/go-sdk/tree/main/examples/actor

[16] EvilCorp Actor Demo - .NET Actor - https://github.com/diagrid-labs/dapr-actor-demos

[17] Dapr-dotnet-actors - ILight Actor code - https://github.com/msfussell/dapr-dotnet-actors

[18] Durable Agentic Workflows with Dapr - https://www.diagrid.io/blog/durable-agentic-workflows-with-dapr

.jpg)